Rust-out: the unfamiliar cousin of burn-out!

Many professional people will have heard of and perhaps experienced burn-out. Like the terms ‘low’, ‘stressed’ and the other commonplace descriptions used to explain what happens when our psychological fuel tank runs empty, what they mean is unique to each person.

However, there is the lesser-known cousin to burn-out which isn’t as often spoken about, but which can, rather paradoxically, have a similar impact. It’s what I like to call ‘rust-out’. Rust-out is not very well known or often spoken about directly, but is hidden in a few commonplace phrases and bits of accepted wisdom that get banded about like ‘the devil makes work for idle hands’ and ‘it’s best to keep yourself busy’.

Rust-out is what can happen to those in the working world when changes happen, which mean that they all of a sudden find themselves without much to do. This can happen for a few reasons. You might find that after a consultancy project, you’re ‘on the bench’ for a few weeks or months. You might find that you join a new company and that it takes a while to get inducted and up-to-speed. People might also face a longer period of inactivity; a person may find their skillset or role is not required in a department or region, and face movement to a new service line or office, or possibly even redundancy.

These challenges in day-to-day life and the level of demand they place on us can lead to a few emotional difficulties if we’re not careful. To understand why, it’s important to look at what helps people remain healthy.

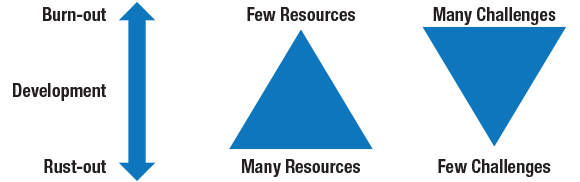

As it turns out, a little bit of stress is often a good thing. Look at the diagram below:

Leo Hendry & Marion Kloep, two psychologists, said that how we develop depends on the challenges we face in life (that’s the triangle on the right; challenges can be a promotion, a new project or the breakdown of a relationship with someone, to name a few). They said that our responses to these challenges, and how we grow from them, depend on the kinds of resources (that’s the triangle on the left; resources include our professional network, self-esteem and confidence, financial resources and knowledge, to mention a few) we have to meet them.

If we face substantial challenges and don’t have enough resources to meet them, we can become anxious, low, can break down psychologically and burn-out. The scale on the far left shows this; lots of demands, few resources, leads to burn-out.

However, if we face few challenges, but have lots of resources at our disposal (the bit at the bottom of the scale), then we can stagnate, have little sense of purpose, become low, perhaps anxious and rust-out. What’s also crucial at this point is that this state of rust-out can persist if a person doesn’t have the resources needed to seek out new challenges that they can apply themselves to. In short, they find themselves in a hole and but don’t know how to get out of it!

It’s important to say also that rust-out, like any kind of emotional issue, can happen in varying degrees. It can be mild, short lasting and not cause many problems; or it can be severe, prolonged and really have an impact.

This concept of burn-out and rust-out can sound a little ‘damned if you do, damned if you don’t’, but the key thing here is that it’s about having enough challenges, with enough resources to meet those challenges. If a person manages to find their way into that goldilocks zone, they can face challenges but gain valuable life experience, confidence and develop as a person from them.

So with this in mind, how do you make sure that either you, or the professionals you manage avoid rust-out, keep developing and remain healthy?

-

When a change happens in your organisation that means you or your team may have to cope with some time away from client-facing work or projects, keep an eye out for signs of rust-out. These may include: agitation, lack of motivation or energy, low mood, anxiety or feelings of tension, complaints of feeling bored or that skills are not being used, staff sickness, lack of engagement in work, worrying about the future and withdrawal from activities previously enjoyed.

-

If it concerns someone you’re managing, consider opening up a conversation with the person about what is going on for him or her from a place of compassion. Be curious, don’t make assumptions, and ask about how they’re doing. If it is a problem with rust-out, consider asking about what they want from their work; what gives them meaning and a sense of purpose in their professional life? What would it look like if they weren’t feeling rust-out anymore? That is, what would they be doing, with whom, where and when?

-

If you’re feeling rust-out, consider how long term this may be. Is this likely to be a brief lull period that will end in the coming weeks or months, or is this likely to be a prolonged period of rust-out?

-

If it’s likely to be a brief period of rust-out, consider what activities you gain a sense of meaning and purpose from in the workplace. What are they, and who do you need to speak to/what do you need to do to facilitate doing those things?

-

If it’s likely to be a more prolonged rust-out, take stock of your resources (financial, social, life experience, confidence). Ask yourself, what gives me a sense of meaning and purpose in my professional life? What is important to me in my professional life? Consider what types of professional activities or roles involve these values. What resources do you need to help you move into that role or activity (e.g. broadening of your professional network, going on a training course, improving your confidence levels)? What can you do to obtain that?

-

Make sure that the resources you provide (or seek for yourself) fit the need. In other words, you need to base your actions in a good understanding of the problem. You can imagine that if your colleague was feeling rust-out because of a lack of challenge in their role, a pep talk to boost their confidence might not be the most helpful thing. To build this kind of understanding takes time, a good collaborative relationship and genuine curiosity. If it’s you that’s feeling a sense of rust-out, reflect on what resource(s) you’re perhaps lacking, and consider what you need to address that problem. Don’t waste time and money investing in solutions that don’t address the root cause. /li>

-

Consider if this something that you can change for your colleague (or yourself), or do you need outside support? For example, does one of your team members seem to have some problems with a lack of confidence or self-esteem that requires more specialist support? Consider whether coaching or psychological therapy may be a helpful tool to help provide the resources to end rust-out, and how you might be able to facilitate access that support. Sometimes expert input is required, and identifying that need earlier will prevent the problem from deteriorating.

If you like our ideas, keep an eye out for our book Staying Sane in Business with its accompanying website sane.works. Both will be out in April.

This blog has been written with the help of our friend and trusted associate, Dr Michael Brown, Clinical Psychologist. We hope to share more of Mike’s ideas over the next 12 months.

Start The Discussion